How Policymakers Can Capitalize on Two Geographical Trends in the Startup Ecosystem

An academic study: VC-backed companies are almost solely responsible for corporate innovation and perform nearly half of total U.S. R&D spending across government, academia, and industry.

Why it matters: American policymakers can capitalize on venture expansion to foster innovation.

Venture capital has left a massive imprint on American life, having served as fuel to create new industries (like biotechnology) and new companies (like Moderna) that have transformed the world. A recent academic study found that VC-backed companies are almost solely responsible for corporate innovation, and venture-backed public companies perform nearly half of total U.S. R&D spending across government, academia, and industry.

The United States needs more of this activity to address challenges like climate change, cybersecurity, and healthcare. The future of American innovation will be determined by how well two geographic trends—one an opportunity and the other a challenge—are navigated by American policymakers and the venture industry. The opportunity before us is that venture and startup activity is spreading into new pockets of the United States—the “Rise of the Rest” talked about by AOL founder Steve Case is accelerating. The challenge we face is that venture and startup activity is increasing overseas, and our share of global venture investment is diminishing.

Geographical trend #1: venture spreads across the U.S.

Our country is blessed to have startup epicenters like Silicon Valley, the greater Boston area, and New York City where venture capitalists deploy billions of dollars annually in new companies. But entrepreneurs are everywhere, and they need capital to grow their businesses.

In the past decade, vibrant venture and startup ecosystems have emerged across the country that are now supporting local entrepreneurs. NVCA has created a “Spotlight On” series to highlight these exciting startup movements and to date has held events focused on Austin; Atlanta; Indianapolis; Miami; Minneapolis; and Salt Lake City. Events for Detroit, Houston, and Raleigh-Durham are scheduled, and more are in the works. In 2019, NVCA also launched VC University LIVE, a new educational program held in emerging ecosystems across the country. Four programs have taken place to date: Ann Arbor, New Orleans, Dallas, and the Raleigh-Durham, bringing education, convening coastal and local startup communities, and shining a spotlight on these ecosystems. The excitement in these regions is palpable, and the data proves out the excitement. For example, from 2015-2020:

- North Carolina saw a 47.7 percent growth in venture investment and last year received $3.64 billion.

- Ohio experienced a 39.5 percent growth in venture investment and last year received $1.45 billion.

- Georgia witnessed a 39.3 percent growth in venture investment and last year received $2.03 billion.

- Florida earned a 31.5 percent growth in venture investment and last year received $1.93 billion.

- Other states that saw growth rates above 20 percent were Connecticut, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Utah, and

Washington.

These trends should be celebrated because it means entrepreneurs can now launch companies throughout the United States, creating jobs and value in new places. Policymakers can support this dynamic in a few key ways:

Cheer local funds: The temptation of many policymakers is to look enviously at mega venture funds in places like San Francisco and hand wring over why more of that capital is not being deployed in emerging ecosystems. That is the wrong approach. VC is inherently a high-touch business – i.e. venture capitalists tend to invest in their backyards as they serve on company boards and act as an outside advisor. What is needed is the proliferation of regional funds that understand the value of the local ecosystem and can work closely with local founders to build a business. Policymakers – whether at the federal, state, or local level – should cheerlead for their local ecosystems. Getting to know the founders and investors is the first step. The second is asking a familiar question to VCs: “How can I help?” Miami Mayor Francis Suarez famously asked this on Twitter, contributing to an invigorated Miami startup ecosystem.

Once the relationship is established, policymakers can:

- Connect entrepreneurs to federal or state agencies that are impactful to startups.

- Bridge the divide between regional research institutions and entrepreneurs who want to commercialize technology.

- Ease state or local regulations that impact entrepreneurial activity.

- Connect potential local limited partners (LPs) in venture funds to VCs.

Local pools of capital: Venture funds in emerging ecosystems often look to a broader limited partner (LP) base, such as family offices and wealthy individuals. But too much capital is on the sidelines because local wealthy individuals and family offices do not understand the opportunity to earn a great return and support the development of their startup ecosystem (thereby creating additional investment opportunities). Policymakers can serve as an important bridge between those sources of capital able to invest in venture funds and those funds investing in the next generation of startups in emerging ecosystems.

Another promising source of new capital is the recently re-funded State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), which received an infusion of $10 billion in March 2021 to support small business financing programs, including state venture capital programs. NVCA has provided recommendations for how this capital can be deployed to support startups in emerging areas. Policymakers – be they federal, state, or local—can play a constructive role in ensuring SSBCI dollars are effectively used for equity investment in high-growth companies.

Small funds, big challenges: Emerging ecosystems tend to spawn smaller and regionally focused funds. The median sized venture fund in the U.S. is $75 million. But that number drops to $24.6 million if California, New York, and Massachusetts are removed from the equation. Many emerging ecosystems are seeing even smaller seed funds in the $5 to $15 million range.

Smaller funds face unique challenges:

- Venture investors are generally compensated on a “2 and 20” model – a 2 percent management fee on the assets of the fund and 20 percent carried interest (profits of the fund). For smaller funds, the management fee barely covers the administrative expenses of the fund and often means investors go without salaries in the early years of a venture firm. This means carried interest is the economic motivator for starting a regional VC fund. In that way, emerging ecosystem funds are hypersensitive to proposed tax increases on carried interest and policymakers should keep this in mind when entertaining tax hikes that are intended to hit other investment entities, such as hedge funds.

- Smaller funds also face many of the same regulatory challenges that much larger funds navigate with relative ease – g. new beneficial ownership requirements; CFIUS scrutiny of foreign LPs and co-investors; and the financial regulatory framework at the SEC that has some funds organized as Exempt Reporting Advisers (ERAs) and others as Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) that have eight times the compliance costs according to an NVCA survey.

The bottom line is policymakers must be sensitive to how policy changes impact these smaller funds that are vital to emerging ecosystems.

Geographical trend #2: venture spreads across the globe

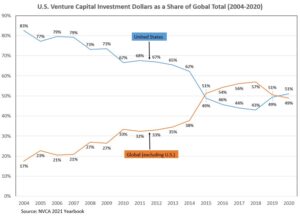

Twenty years ago, the United States startup ecosystem received about 90 percent of global venture capital investment. Venture capital was invented in the U.S. after all, and the world’s top entrepreneurs generally thought they had to come to this country to raise capital for risky but promising endeavors. Other countries paled in comparison to the U.S.’s capital markets, protection of intellectual property, cultural and legal tolerance for failure, basic research investment, and other important attributes.

Then other countries used the U.S. playbook and reformed their laws to draw startup ecosystems to their shores. Countries reformed their immigration laws to create startup visas to attract the world’s best entrepreneurs; tax regimes were modified to benefit early-stage companies; and bankruptcy laws were reformed to not punish risk-taking entrepreneurs.

Around the same time, the United States made changes that negatively impacted our competitiveness: immigrant entrepreneurs struggled to launch companies in the U.S. because of a lack of startup visa; basic research investment stagnated; and foreign investment into U.S. startups faces new national security hurdles.

The sum of these developments is the U.S. now attracts about 51 percent of global venture capital—a nearly 40 percentage point drop in a couple decades. To be fair, VC investment into U.S. companies continues to rise as an absolute number, but our share of the global pie is shrinking. There are new pools of capital around the world, and entrepreneurs can remain in their home countries to launch an innovative new company.

Policymakers should be alarmed by this trend and redouble efforts to make the U.S. the best place in the world to launch a new company. Reforms in these areas would go a long way:

Immigration: It is unnecessarily difficult for a foreign-born entrepreneur to launch a high-growth startup in our country. Uncle Sam is shooting himself in both feet as entrepreneurs who struggle to come to the U.S. end up creating their companies in other geographies. Congress should pass a “startup visa” like Rep. Zoe Lofgren’s Let Immigrants Kickstart Employment Act. The bill would create a dedicated visa category for foreign-born founders who are backed by VCs or other investors, thereby ensuring immigration law is not an impediment to company creation.

Competitiveness: U.S. technology dominance is underpinned by successful collaboration by the public and private sectors – technologies like GPS and companies like Moderna owe much of their success to forward leaning commercialization efforts. But the U.S.’s investment in basic research and commercialization has dwindled as a proportion of overall R&D funding. We should reverse course so the seeds of growth are planted now. The Senate-passed Endless Frontier Act (re-branded as the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act) is a commonsense approach that increases investment in research, training, facilities, and entrepreneurship to support American leadership in emerging technology areas.

Tax: Venture-backed startups are different than other companies. The startup model means these companies sell minority equity stakes to outside investors to fund oftentimes radical innovation and in the face of low odds of success, all while losing money for years. With this model comes unique policy considerations, especially in the tax space. Policymakers should approach tax policy with more sensitivity to how high-growth startups are organized rather than focusing on large companies or traditional small businesses.

The good news is there are champions in Congress who are working to reform the tax code to encourage new company formation. For example, the IGNITE American Innovation Act from Representatives Dean Phillips (D-MN) and Jackie Walorski (R-IN) would allow startups to monetize net operating losses (NOLs), thereby financing job creation and R&D. Another example is the American Innovation and Jobs Act from Senators Hassan (D-NH) and Todd Young (R-IN), which would increase the ability of young companies to access the R&D tax credits.

These policy proposals would set the United States on a course of increased competitiveness vis-à-vis other countries. Beyond job creation, home grown innovation is a tremendous national security asset as it domiciles companies with critical technology in our country and subjects them to U.S. laws.

The Path Forward

The future of venture-backed companies is bright. New industries will be spawned. Diseases will be eradicated. Lives will be improved. But the degree to which this all happens both in the United States and spread more equitably across our country is not yet determined. That is why the moment is now for policymakers and the startup ecosystem to stand together to make the United States the best place in the world to launch a high-growth company

Jeff Farrah served as General Counsel at NVCA, where he advocates before Congress, the White House, and agencies for pro-entrepreneurship policies and leads in-house legal matters for the association. He loves working at the intersection of venture, public policy, and the law. Jeff served as Treasurer of VenturePAC, the political action committee of NVCA.